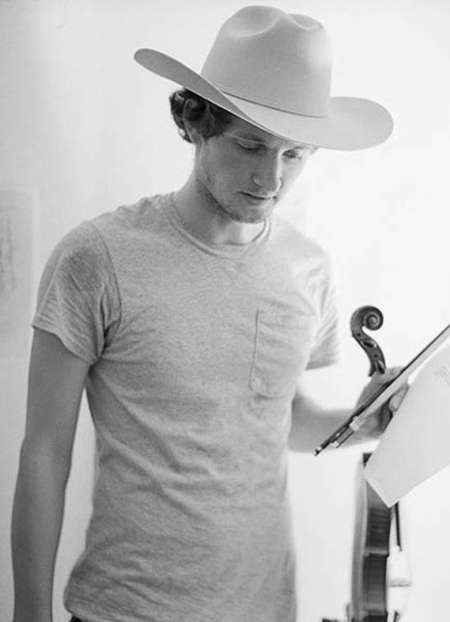

Sam Amidon

Website: www.samamidon.com

Folk, Indie: Vermont, New York City

Sam Amidon reclined in a chair, folded his arms over his eyes, and swiveled quarter-turns back and forth as we listened to a take of Wild Bill Jones. The story was unfolding, genuine and somber. Wild Bill had just been shot, and my eyes opened wide as Sam’s voice on the playback suddenly let out an awful, extended moan: Aaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhh!

“That was a good one.” Sam said with a grin.

I wondered just how much was going on inside that mind. And just how he’d gotten to this point—working on his third folk-inspired CD in the last three years.

“When I got into folk songs it was in the same way that a lot of other indie people have gotten into it. All these field recordings were re-issued, the Harry Smith Anthology was re-issued, Alan Lomax; Cat Power recorded a Mississippi John Hurt song on her Covers record. People who were into free jazz started listening to it, The Wire started writing about folk stuff.”

“So, the hipster record store in Brattleboro started putting these old-time CDs on their shelves and I’d pick it up and go ‘Why are they selling this? I thought this was an indie rock and free jazz store.’ And I would buy the CD and take it home, and we’d have the original LP at home and I knew a lot of the songs.”

It was such good fortune that Sam invited me to the studio that day—having the pleasure of hearing a song or two that will be on an upcoming CD. After the session we sat down and talked. And there was lots of energy and excitement in what he told me.

“My parents were both musicians. They were part of the folk revival in the ‘70s. They lived in Vermont and were part of a group called Bread and Puppet Theater, which was sort of like this leftist, avant-garde big-puppet theater company. They weren’t puppeteers, they were singers. They performed at folk festivals and my dad led a children’s choir and they were teachers; it was a big assortment of things. They were really into folk dancing and all that. And many of their friends were also music teachers and also folk singers, and dancers, and musicians, and storytellers, and this whole gamut of folkie practices, so I grew up singing with them. Now a lot of the songs I’m doing come from that tradition.”

Singing, traveling with his parents: great fun for the young Sam Amidon. In one way, yes, he did grow up with folk music. But in another way he wasn’t consciously into it. And he didn’t quite consider himself a singer.

“My parents are really into sacred harp singing, shape-note singing, which is this tradition of choral singing that’s outside the traditional sphere of choral music singing; kind of ‘folk choir’. So I did that, singing, because it was just in my house…but I was really already thinking of myself as a fiddle player.”

He was also cultivating an affinity for free jazz violin, and the desire to study in New York. Soon he’d get there. Summertime in Harlem. And ultimately, it was an empty house for Sam. His housemate (childhood friend and another supremely talented musician, Thomas Bartlett) would be touring for almost the entire season. With all that time and space not only did Sam study free jazz violin, but he also began teaching himself how to play the guitar—setting folk songs to the instrument to help him learn. He’d come up with a riff or a melody and play it for days straight. And almost accidentally other melodies and lines would fall on top. Sometimes perfectly. Other times a clash, unintended—but equally terrific. For Sam, these were origins of the folk CDs he has since created. But more to the time, it allowed him personal discoveries and the chance to reach out, musically.

“I was in Doveman doing the indie rock thing, and I joined a band called Stars Like Fleas, this pretty amazing group. They’re an indie rock band but they use a lot of free jazz influence, and I was able to do a lot of free improvising on the violin in that group. I played in Irish sessions and gave fiddle lessons, and that was my living. It was incredibly exciting for me. It was exactly what I had come to New York to do.”

And beyond all of this, Sam was drawing comics. And break-dancing. And making bizarrely hilarious videos with a camera his parents had given him (search “Sam Amidon” on YouTube and watch, please). It was a brilliant assortment of art.

Then all those disparate things somehow converged, as Sam began performing folk songs at shows.

“I came to New York to escape the folk thing and to become part of the rock scene or the free jazz scene and it… kind of backfired. I got here and everybody was into folk music. I was like, ‘well, I can play some of those songs or whatever.'”

“So that was a very weird process of…the indie rock hipster continuum of embracing more and more of the really dorky things of my youth that I was embarrassed to tell people.”

You’ll hear just how much Sam embraces those things, and also how much his other influences come in on his CDs (But This Chicken Proved Falsehearted and All is Well) and during his shows.

“As far as the performances, I just feel like sitting there playing banjo and singing or playing the guitar and singing has got to be boring for the audience. To be able to feel like I can get up and tell some stories or scream or dance around gives it a component that weirds people out a little bit, and makes me feel a different way.”

I think more than anything, what catches me is Sam’s voice. It’s so well suited for storytelling and lamenting that sometimes it almost hurts to listen. It’s difficult to explain exactly, but there's something very human and something easy to relate to—something very alive and tender and honest-hearted about his voice.

And it’s the storytelling part of Sam. He really does it with each song. No, he didn’t write the melodies. The lyrics aren’t his. But he’s put something of his own particular nature into the songs. And you can do that with folk. Maybe that’s even the purpose.

“These songs have been edited for hundreds of years. That’s what the process has been. It’s like somebody forgets a verse because it didn’t mean much to them, or they change a line because they forgot it. So that is one thing I love about these songs is there’s so much left out, and yet they’re so suggestive.”

“You can hear them say that a lot in the field recordings. They have all these stories which cannot be true about where the song was invented. They’ll say (switching to an old, nostalgic voice) ‘this song was written at the uhh battle of…DURING the battle, and he played the tune’”…

“There’s no source. That’s the thing. People always think that ‘oh it’s authentic’. I mean, there’s a sense of authenticity, of ‘the old guy on the hill’ or whatever, but the reality is he’s not the first either, you know? He learned it from somebody else. It’s a much more mysterious path.”

Sam mentioned that although it is true he grew up with a lot of folk songs, it’s a little misleading; that he really has no claim to the music that somebody else doesn’t; that he found them on iTunes, and not trudging through North Carolina; that it was just links from one person to another.

Yet there’s something there—in his voice and how he tells the story—it’s like he’s made himself into one of those links back to another link, back to another. Folk music lends itself to that. It’s a music that’s meant to survive. With Sam’s music I can hear that.

“At some point I’m going to have to find some other thing to do, but at the moment I don’t feel like it’s exhausted itself.”

“It has a vibe, and it’s an amazing feel.”

{april 2009}

All stories are copyright of Gregory Koutrouby and A Thousand Stories unless otherwise noted.